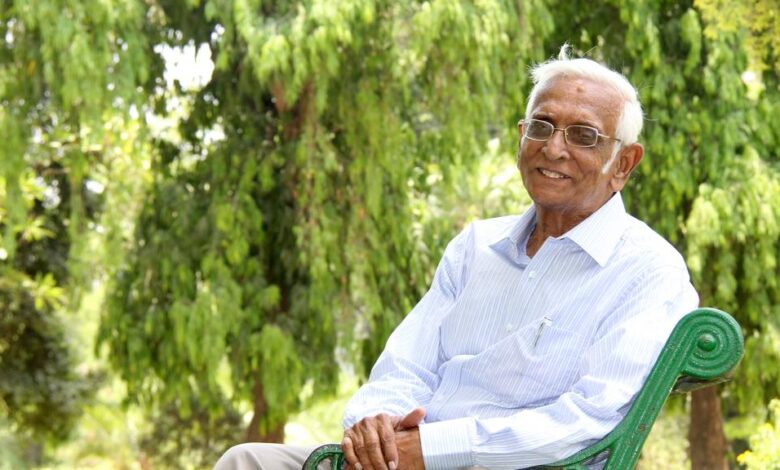

Indian Muslim scientist, author of botani, on the ‘Quranic plants’

We speak to an Indian scientist and author of botani, who is dedicated to interpreting the relevance of the plants mentioned in the Quran.

It was possibly inevitable in some ways that M I H Farooqi MSc, PhD, would end up writing books on the hadith and Qur’an plants. His origins are botany and Islam.

Not only has the 79-year-old scientist dedicated his professional life to the study of plants and their uses, he is also the intellectual product of Aligarh Muslim University, one of India’s most prominent Islamic academic institutions, as well as being the son of Al Haj Maulana Abrar Husain Farooqi, a highly known Islamic scholar.

It was some decades, however, before the author of Medicinal Plants in the Traditions of Prophet Muhammad and the best-selling Plants of the Quran turned his attention to the finer questions of Quranic botany, such as the source of the Israelite-sustaining manna, the confusion surrounding the true identity of Quranic camphor and the identification of plant species associated with paradise (jannah) and hell (dozakh).

Mohammed Iqtedar Husain Farooqi, 25, left his hometown of Barabanki in 1961 and moved to Lucknow, the town he still calls home.

It was here that he joined the National Botanical Research Institute of the Indian Government, first as a scientific assistant and eventually as assistant director, dedicating a 35-year career to the chemistry, economic botany and commercial potential of plants.

Farooqi may be known for his Plants of the Quran in the wider world, but his reputation in botanical circles rests on the authorship of more than 120 research articles, the first published in 1962, as well as for reference works such as his Dictionary of Indian Gums and Resins and Indian Plants of Commercial Value.

In the late 1970s, when he submitted an article about manna, a life-sustaining substance mentioned in the Bible and the Quran, to various Urdu-language newspapers such as Qaumi Awaz of New Delhi and Siasat Daily of Hyderabad, Farooqi first wrote about Quranic plants.

“There has been a lot of work on the plants of the Bible, but I was one of the first to start researching the plants of the Quran in this way, and fortunately I was encouraged by Maulana Abul Hasan Ali Nadvi [one of the greatest subcontinental scholars of Islam in the 20th century] to write my articles in the form of a book,” Farooqi explains.

“The commentators of the Quran, the mufassirun, had applied their minds to the identification of some plants, but unfortunately, none of the commentaries provide a scientific description.”

The chapter on manna by Farooqi is an example of how the scientist tried to achieve just that.

It starts with the Quranic name of the plant, Al Mann, and then lists its common names, such as turanjabin and kazanjbin in Arabic, before listing the likely botanical names of the plant and examples of where it appears in the Quran, such as in verse 57 of the surah known as “the heifer”:

“And We gave you the shade of clouds and sent down to you manna and quails, saying: ‘Eat of the good things We have provided for you:’ (But they rebelled); to Us they did no harm, but they harmed their own souls.”

Farooqi then embarks on a detailed description of how Western scientists have described the plant in Islamic tafsir, or interpretation, attempts to identify it, the etymology surrounding its name, and even how to know substances that may refer to manna are in use.

The result is a cross between an entry in an encyclopaedia and books such as the groundbreaking Flora Britannica by Richard Mabey, which is a kind of cultural and botanic compendium.

There is always the added element of Islam in Farooqi’s case, and while the scientist maintains that his work is not a commentary on the Quran or that his ideas are an attempt in any way to alter its meaning, there are instances where he appears to have helped to clarify certain long-running misunderstandings.

“There are 22 plants that are mentioned by their specific names in the Quran, whereas in the Prophetic tradition, about 50 plants are mentioned, mostly well-known medicinal plants – for example, the black cumin, the toothbrush tree, the senna, chicory, cress seeds, aloe, fenugreek, marjoram and saffron also,” the scientist says.

“Many of the plants mentioned in the Quran are common to Arabia and India; in fact, many of the plants that are mentioned in the Prophetic tradition, in the hadith, were imported to Arabia from India long before the advent of Islam.”

“So identifying the common plants was easy, but identifying the plants that are associated in different Quranic verses with paradise, jannah, and with hell, is very difficult, because in each of the commentaries of the past, they have given their own ideas, and the new interpretations, which I have given, have not always been accepted.

“There is a verse in the Quran that says that all good Muslims, when they reach jannah, will be provided with a drink in which camphor will be mixed, but this is not understandable,” he says. “Camphor is a toxic substance, and if you mix even a small amount with water, you cannot drink it.”

The answer from Farooqi is not to describe the Quran’s kafur as camphor, but as henna or Lawsonia inermis.

“Many people do not accept the reinterpretation, but I am fortunate that some well-known Islamic scholars, including those from the Islamic University in India, have agreed with my interpretation and have said that my work has done much to remove confusion.”

The Quranic sidr, which has been commonly understood to refer to the tree we now know as Ziziphus spina-christi, is two of Farooqi’s other controversial interpretations, but which he maintains is actually the cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani), and the zaqqum, or tree of hell, which the scientist has identified as Euphorbia resinifera.

The first edition of Plants of the Quran was published in 1986. Since then, it has gone through nine editions and been translated into at least nine languages, including Urdu, Hindi, Kannada, Malayalam, Farsi and Bahasa (from Indonesia).

Farooqi says that almost 10,000 copies have been sold, but he says it is impossible to put a real figure on the sales, because without his permission, the volume has been reprinted many times.

The success of Farooqi’s Quran- and Hadith-related publications has led to international recognition, although he remains a “humble scientist.”

In 2010, he received the congratulations and thanks of Mohammed VI, the king of Morocco; in 2011, he was awarded US$25,000 (Dh91,829) by Qaboos bin Said Al Said, the sultan of Oman.

The new project for the retiree is a book on the animals mentioned in the Quran, which he hopes will be ready for publication this year.

“Mostly, I write now. Every few days, I get emails from newspapers and magazines across India asking for articles – I am more busy now than I was when I was working full-time,” he says.

“My wife complains that I did not give enough time to my family when I was working, and now that I am not [working], she says it’s just the same.”

From some news agency